About 25 years ago, I went to a gig at one of my favourite London venues, the Charing Cross Astoria. I can't remember who was headlining, but I do remember hearing on the local radio that it was worth turning up early as the support band was a bit special.

There were probably no more than a few hundred people in the audience. The band was led by a very charismatic young singer, and while they were perhaps a bit 'mainstream' for a hardened indie rocker like me, you could see there was, indeed, something special about them. The audience loved them and unusually for a support band, they got raucously called back for an encore.

That charismatic young man's name was Chris Martin, his band was called Coldplay, and they went on to conquer the world.

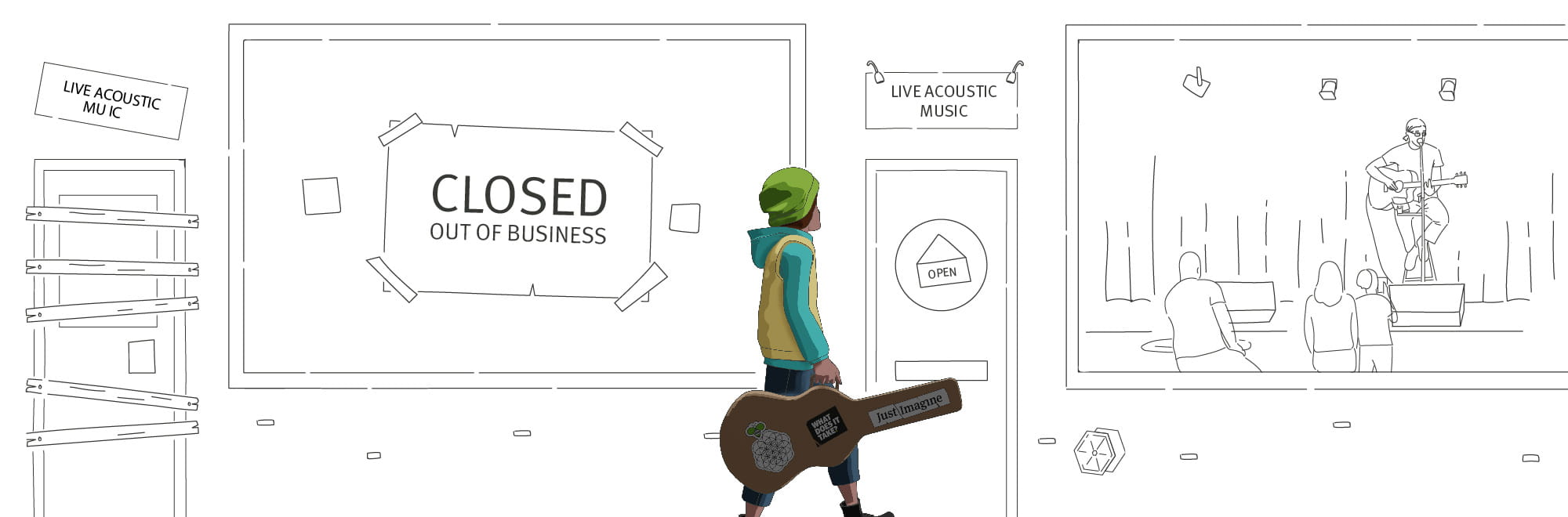

Sadly, the Charing Cross Astoria is no more. Yet another small independent venue, crucial to the incubation of emerging indie talent, defined by a spirit of independence, experimentation and creativity, lost forever. It is a story that is playing out all around the world.

If independent music signifies the 'essence' of each new generation, how do we design legacy entertainment venues that nurture the creative soul of a city?

Changing 'records' in the industry

The Music Venue Trust, a charity established to protect and promote the interests of the Grassroots Music Venue (GMV) sector in the UK reported that 125 venues closed in 2023 alone. Meanwhile, in Australia, according to the Australasian Performing Right Association, over 1,300 small and medium sized music venues have closed since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic – that's a third of the entire sector. And New Zealand's live music scene was already 'on the rocks' even before the pandemic started.

The GMV sector is vital in nurturing the future of independent music. A rock band is not just an assembly of talented musicians, it is a 'gang', with shared values and experiences. Just like a start-up in the business world, the band members need space to learn their craft, experiment, and to be discovered. Many of the great bands, now household names, got their first breaks through chance discoveries in small venues. So, without it, where would future breakthrough artists go?

The demise of the traditional rock band has crept up on us over the past decade or more, driven by fundamental changes in the dynamics of the music industry. The rise of streaming services has had a profound effect; global sales of physical music products are down over 80 per cent this century and record companies are increasingly inclined to invest in solo performers, more likely to be discovered through TikTok or Instagram, than by building a live following.

With the loss of earnings from physical products, live music has, if anything, become more important than ever as a revenue generator. However, a huge chasm has emerged where well-established acts can charge megabucks for stadium tours, and some of the more critically acclaimed new bands are squeezed out and are genuinely struggling to make a living.

How can the industry keep up with these changes through the power of design? What can designers, engineers and advisors integrate within the walls of these venues that cannot be seen, heard, or felt through our screens and headphones?

The power of music: vibes and drive

The demise of the GMV sector is being hastened in many of our cities by the attitudes of planning and licencing authorities, and pressure on developers to get better returns from their real estate.

Does this matter? Absolutely! For many countries, the music industry contributes hugely to their economies, but just as significantly, it plays a major role in the projection of soft power and influence around the world. Most importantly, the indie music scene creates a vibe that feeds into a wider city ecosystem that provides a pathway for fledgling bands from 'emerging' to 'world domination'. So, how important is the role of small venues in supporting and nurturing a culture that translates the sense of soul from 'small' to 'large'?

The symbiotic relationship between minor and major venues is essential. And breaking that connection between the two will not only hurt, but potentially cause the slow death of the soul of a culture or a community.

Designing for the soul

Grassroot venues and the development of a vibrant music heritage can play a major part in increasing tourism and city branding, especially for younger visitors who are fundamental to a thriving nighttime economy in major cities.

A great venue will attract a more diverse, multigenerational mix of people who will want to stay to enjoy bars, clubs and restaurants. And a creative neighbourhood, whether it be an imaginatively designed new precinct or repurposing of a disused post-industrial quarter, draws creative talent to live and work in the city.

There are cities which are already bucking the trend. Initially developing as a counterculture to the Nashville country music scene, Austin, Texas in the US has fully embraced its reputation as the 'Live Music Capital of the World' with an astonishing 250 live music venues.

Today, over 160,000 people from all over the world fly in for the annual South by Southwest Festival and 450,000 for the Austin City Limits Music Festival. The city has become a beacon of hope for aspiring musicians attracted by the creative culture, liberal politics, and low cost-of-living. It's all about making those wise and soulful investments.

Brisbane, Australia is another example of a city nurturing the independent music scene. As a newcomer to my adopted city, I have been both intrigued and delighted to see a booming live music scene. The music scene is thriving where other Australian cities' venues are barely surviving.

New venues have proliferated in recent years, including the new Fortitude Music Hall opened in 2020 and the revitalised 135-year-old Princess Theatre, which reopened its doors in 2021. These new venues join a plethora of existing grassroots venues, steeped in tradition, and often jostling cheek by jowl in the city's cultural quarters.

What is Brisbane doing right and what can we learn from it? And more importantly, how can we harness and leverage it into the design of new venues and precincts? It is a combination of enlightened planning and entrepreneurial spirit. Brisbane City Council was the first in Australia to designate a Special Entertainment Precinct, which was done specifically to support local live venues.

The council recognises both the commercial and cultural values that the precinct brings to the city. There is also a feeling of mutual support between the venue operators – many of the larger venues share ownership in the smaller venues which can act as feeders for emerging talent. And crucially, there is a critical mass, creating a symbiotic relationship where venues support each other.

With the Olympic and Paralympic Games coming to town in 2032, Brisbane is turning its focus to developing exciting new venues in the city. Will it be possible to retain the unique character of existing venues and translate this into shiny, new ones, that nurture the creative soul of the city? I think it is not only possible, it is essential.

Ultimately, grassroots music venues have a vital role to play in defining and nurturing a city's unique character. And as designers, engineers and advisors, it is our responsibility to translate this spirit into how we design soul into new venues and precincts.

This blog was authored by: Peter Ayres